Can Hot Water Freeze Faster Than Cold Water?

The Mpemba Effect Explained

It sounds like a contradiction to everything we’ve learned in science: can hot water freeze faster than cold water? Surprisingly, under specific conditions, yes—it can. This counterintuitive phenomenon is known as the Mpemba Effect, and it has fascinated scientists and everyday observers for decades.

In this article, we’ll explore:

- What the Mpemba Effect is

- When and why hot water may freeze faster

- Scientific experiments and theories

- Real-world examples and implications

- Whether this effect still holds up to scientific scrutiny

What Is the Mpemba Effect?

The Mpemba Effect refers to the observation that hot water can sometimes freeze faster than cold water under certain conditions. The effect is named after Erasto Mpemba, a Tanzanian student who in 1963 observed this strange behavior while making ice cream. His observation, initially dismissed, was later confirmed by physicist Dr. Denis Osborne, leading to scientific studies on the phenomenon.

Definition:

The Mpemba Effect is the condition in which initially hotter water freezes faster than initially cooler water under otherwise identical conditions.

Is It Real? The Scientific Debate

The Mpemba Effect has been replicated in some experiments, but not consistently. That’s why it remains a subject of debate among physicists. Some researchers claim the effect is real but rare, while others argue it’s an observational artifact caused by inconsistent conditions.

Despite decades of studies, there is no universally accepted explanation. However, multiple theories try to explain why it might happen.

Possible Explanations: Why Hot Water May Freeze Faster

1. Evaporation

Hot water evaporates faster, reducing the overall volume that needs to freeze. Less water = faster freezing time.

2. Convection Currents

Hot water creates stronger convection currents, which may help distribute heat more evenly and allow faster cooling.

3. Dissolved Gases

Hot water contains fewer dissolved gases like oxygen. These gases can affect thermal conductivity and freezing behavior.

4. Supercooling

Cold water is more prone to supercooling—dropping below 0°C without forming ice—whereas hot water may freeze sooner by avoiding this phase.

5. Thermal Conductivity of the Container

Hot water may melt ice beneath its container in a freezer, improving contact and speeding up the cooling process.

Experimental Evidence

While experiments have produced mixed results, some notable studies include:

- Mpemba & Osborne (1969): Their experiments confirmed the phenomenon under specific circumstances.

- Royal Society of Chemistry (2013): Held a global contest to explain the Mpemba Effect, encouraging thousands to replicate it.

- University of Alberta (2016): A study showed that differences in hydrogen bonding in hot water could make it freeze faster.

Still, many scientists have failed to reproduce the effect reliably, pointing to the complexity of variables like:

- Container shape

- Water purity

- Ambient temperature

- Freezer airflow

Key Variables That Affect Results

| Factor | Influence on Freezing |

|---|---|

| Water Temperature | Determines starting point |

| Volume of Water | Affects total freezing time |

| Container Shape | Impacts heat transfer |

| Air Circulation | Can speed or slow cooling |

| Surface Area | More surface = more evaporation |

| Freezer Consistency | Temperature may vary |

Because of these variables, you may or may not see the Mpemba Effect if you try this at home.

Can You Try It at Home?

Yes! Here’s how you can experiment safely:

Simple Mpemba Effect Experiment:

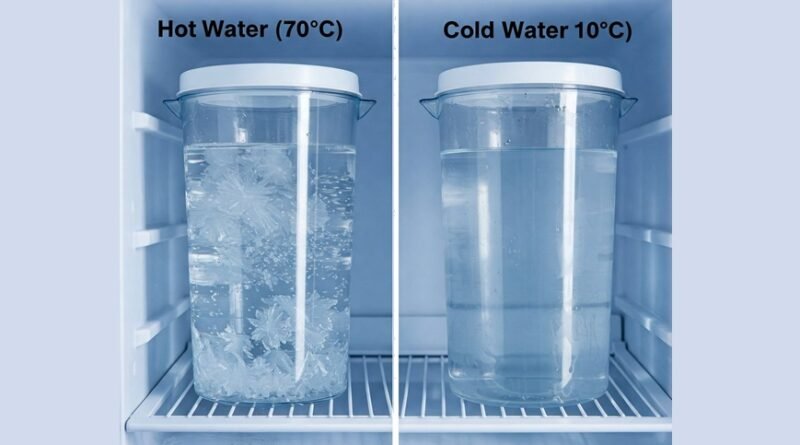

Materials:

- Two identical containers

- One filled with hot water (~70°C)

- One with cold water (~10°C)

- A freezer

Steps:

- Place both containers in the freezer at the same time.

- Monitor every 15–30 minutes.

- Record which one freezes first.

Note: “Freezing” can mean when ice starts to form, when it’s solid throughout, or when it reaches 0°C—each can yield different outcomes.

Real-World Applications

Although the Mpemba Effect has limited practical use, it raises important questions in physics, thermodynamics, and science education. It’s a great example of how intuitive logic can sometimes be challenged by observation.

Applications include:

- Ice cream making (original context)

- Cryogenics and fast freezing in food industries

- Teaching scientific reasoning and experimentation

What Modern Science Says Today

Most scientists today accept that:

- The Mpemba Effect may occur, but only in specific, controlled conditions.

- It is not a general rule, but rather an exception.

- Its mechanisms remain complex and not fully understood.

The phenomenon continues to inspire curiosity, debate, and experimentation in physics labs and classrooms around the world.

Explore:

Conclusion

So, can hot water freeze faster than cold water? Sometimes—under the right conditions. The Mpemba Effect reminds us that even the most basic scientific assumptions should always be questioned and tested. Whether you believe it or not, this strange freezing behavior continues to stir debate and fascinate scientists over 50 years after it was first observed.